As “pilgrims of hope,” “song is existence”

Regarding the happy coincidence of the Jubilee 2025 and the celebration of the 800th anniversary of the Canticle of Brother Sun composed by Saint Francis of Assisi

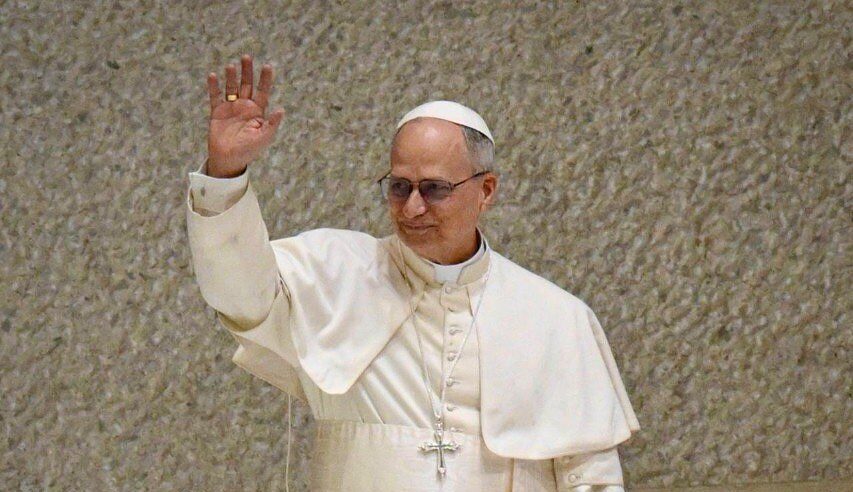

Precisely on Angel Monday, with the immense joy that fills the Octave of Easter, we trust that our beloved Pope Francis, after his intense pontificate and at the end of his illness and persistent pain, has departed into the arms of God the Father, as if confirming with the gift of synchronicity an invitation to appreciate the offering of his life consecrated to loving service as pastor of the Church, a sign at the same time in which the full meaning of existence, centered on hope in the risen Jesus Christ, is revealed to us. Of course, we feel sorrow at Francis’s passing, but, following some lines of Josef Pieper’s thought, there is in the inner conviction that the moment of consolation for grief entails what could be called a silent joy. Such joy is a tacit assent in the present and an openness that trusts in love and its expectation. Spes non confundit, “hope does not disappoint” (Romans 5:5), is the motto of this Jubilee Year. And now, in the third week of Easter, we joyfully arrive to celebrate with profound emotion the election of the successor to the Chair of Saint Peter and his mission as Vicar of Christ, Leo XIV, whose first greeting is the same as that of the risen Jesus and which he addresses to all hearts, to all our families, “to all people, wherever they may be, to all nations, to all the earth”: “Peace be with you… an unarmed peace, a disarming peace, humble and persevering, which comes from God, from God who loves us all unconditionally.”

For those who accept the events of each day as a gift that fosters gratitude and thus seek to contemplate reality with a “simple eye” – “healthy” or “clean,” depending on the translation of the Gospel (Matthew 6:22) – an attentive gaze imbued with love welcomes and celebrates Creation with smiles, discovering beauty and correspondences between the diverse components of the “common home” in which we live – as Pope Francis aptly calls it in Laudato si’ – perhaps like a modest inner echo that seeks to faithfully follow Scripture itself: “God looked at all that he had made, and behold, it was very good” (Genesis 1:31a). And that same gaze with pure eyes leads us to feel in our spirit – almost drawing it in our imagination – the luminous and beautiful smile of God the Father, who contemplates with pleasure all the good he has created; That all-good, full of wonders, which, as the beginning of St. John’s Gospel reminds us, “was made through the Word,” “and the Word was God.” Continuing with the Johannine text, it is also announced, to our amazement and greater joy, that “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us,” precisely thanks to the kenosis of the Son, who immeasurably intensifies the supreme good with the lavish love poured out in the ultimate sacrifice to give us life in fullness.

Perhaps some skeptics consider this festive vision tinged with naiveté and even conveniently selective, seeking to evade or choose to be short-sighted and even blind to the immense historical problems that afflict and have afflicted our civilization, which would relativize or question its usefulness and practicality. However, that same contemplative gaze, with its inevitable celebration of creation, harmonized by faith and its assent that discovers the gift and response of love, is at the same time a serene visual acuity that seeks to sensibly understand the shocks and contrasts, often calamitous and horrendous, of history. “If your eye is single—clean and sound—your whole body will be filled with light,” completes the Gospel passage given to us by Saint Matthew.

We aspire to live in harmony, joy, and balance, sharing the common home of Creation. But how can we make true and fruitful coexistence possible between those who—to quote Mariano Picón-Salas—can barely bear history and those who seek to shape it, even direct it, in their excessive desire to possess and dominate? We can think of an ideal of culture as a yearning for elevation and harmonious coexistence, and thereby guide our work toward these goals. It is even more necessary to remember that in the tension of life, the harmful human errors caused by intolerance and resentment, selfishness and ambition, indifference and frivolous chosen ignorance persist… In trying to build a path toward what we desire as true progress or shared human well-being, how can we set aside and fail to keep present in the exercise of conscience the problems that need to be faced and understood with dedicated attention in the historical past and in our present: poverty and extreme marginalization causing famine and helplessness, which frequently pushes us to inevitable migrations; the repeated labor exploitation, the unsettling unemployment and the negligent degradation of nature and the environment; the human degradation caused by drug use, the infamous human trafficking and perverse child abuse, ominous and inconceivable activities that even become lucrative businesses; the authoritarian and totalitarian regimes that crush, torture, segregate and persecute peoples, communities and individuals; the barbaric war, the raids and genocides, even systematic ones like the Shoah and the Holodomor, to name just a few? The heartfelt words of Benedict XVI resonate in our memory once again during his visit to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in 2006, when he tells us that none of this is past or distant to any of us. In that particular and impressive space of memory of the exercise of cruelty inflicted by human beings on other human beings, the Holy Father then asked himself questions of profound pain, so similar to those we insist on asking when we pass through incomprehensible “valleys of shadows” in history and in the contexts in which we live: “Where was God in those days? Why did he remain silent? How could he tolerate this excess of destruction, this triumph of evil?” But Pope Benedict, deeply convinced that “God is love” (1 John 4:8), at the same time responded to us:

“We cannot fathom the secret of God. We see only fragments, and we are mistaken if we wish to judge God and history. In that case, we would not be defending humanity, but would only contribute to its destruction. No; ultimately, we must continue to raise, with humility but perseverance, this cry to God: ‘Arise! Do not forget your creature, humanity.’ And the cry we raise to God must, at the same time, be a cry that penetrates our very hearts, so that the hidden presence of God may be awakened within us, so that the power God has placed in our hearts may not be covered and drowned within us by the mire of selfishness, fear of men, indifference, and opportunism.”

The personal call is directed to our own conscience in the present. With humility, that is, in the recognition of the fragility and limits of the human condition and in the willingness to walk and be open to the truth; in the journey through an unintelligible darkness that threatens to lose us; in the complete stripping away of the layers of the ego, distracted or determined to remain external to judge only vertically, to assign blame, or, conversely, to excuse without understanding; in that silence that only waits, conscience manages to glimpse the certainty of life that is love, “the hidden presence of God.” Beyond the often uncontrollable and indecipherable circumstances, perhaps the path briefly describes the route of the mystery of the cross, and it itself gives us some keys to consequent actions: free will in accepting the path, sometimes not chosen, that leads to the surrender and offering of our being and our actions, which brings us back to the original meaning of sacrifice, that is, making things sacred, making them holy, all within the permanence of love. Our perspective changes, and the vocation of fraternal service and sharing emerges as a natural fruit. Don’t both seem to describe the imperative need for these steps of humility to also attend to and seek to respond, perhaps to try to resolve in our particular spheres and on a minimal personal scale, the problems of humanity and our common home, so that truth and love may finally meet, so that justice and peace may embrace (cf. Psalm 85:11-14)?

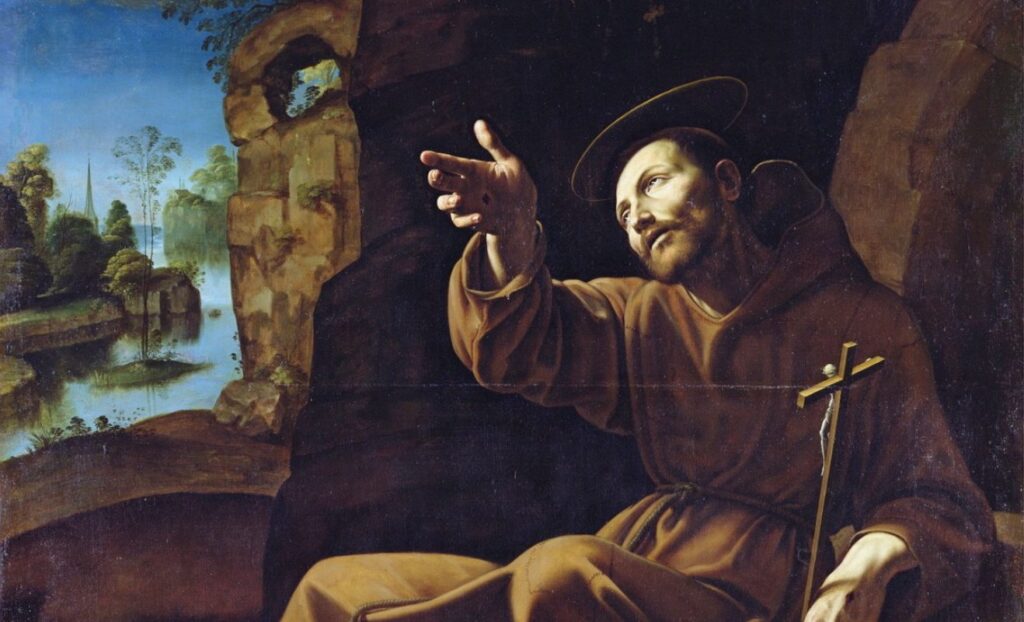

Exactly eight centuries ago, Francis of Assisi, the saint admired for his extraordinary joy that still captivates us today, as if hinting at a supernatural formula we long to discover, went through dark and painful periods, particularly during the final years of his life’s journey, when the Order of Friars Minor, which he had unwittingly founded, was growing and expanding to various regions beyond his native Umbria. Not only was his body weakening from the various illnesses he suffered, but his ideal of living the Gospel to the letter seemed to dissipate among his more recent followers with different aspirations, the brothers whom the Lord himself eventually gave him. Perhaps there was a softening of his way of life that, for his demanding and personal search, seemed unthinkable; a great tribulation that he could neither relieve nor understand invaded his soul. Towards the autumn of 1220, he dictated to Brother Leo, his constant companion, the allegory Of True and Perfect Joy (Fonti Francescane [FF] 278), a suggestive meditation that reveals to us that this joy does not consist in a perhaps charismatic good humor, nor in praiseworthy and magnificent triumphs and satisfactions, even spiritual ones, but in fidelity and awareness of being on the path that allows us to patiently fulfill the will of the Lord and always see his face and image in each brother, despite receiving misunderstandings, rejections and persecutions; without a doubt the text constitutes an interesting mirror of the beatitudes that Jesus communicates to us in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5, 3-12; Luke 6, 20-23), with its surprising paradoxes that open a different space in the soul for understanding. Shortly after experiencing these tensions, following the approval of the Rule of the Order on November 29, 1223, by Pope Honorius III, Francis of Assisi renounced his role as a founding father and dedicated himself solely to living as a brother in his apostolic journeys and solitary retreats. He sought the humblest path to rediscover himself, as if trying to follow even more closely the inspiration of Jesus’ kenosis. Shortly after, around September 17, 1224, on Mount La Verna, upon witnessing the vision of a winged seraph during Lent, the Archangel Saint Michael, he obtained the unprecedented grace of being imprinted with the stigmata, the wounds of Christ crucified, a mysterious gift of immense love and pain that, as a humble living representation of the Savior, he received and carried within his body in intimate secrecy. Of course, these mystical wounds caused him physical suffering, to which were added the severe ailments of his various illnesses and his low spirits regarding the present and future of the Order of Friars Minor, a deep regret that made him question the fruits of his mission, perhaps reflecting on the apparent failure of his journey. In the tradition of the story recorded in Mirror of Perfection (100-101 and 120; FF 1799-1800 and 1820), during the winter of that same year 1224 and early 1225, in a small mat cell near the Convent of San Damiano, Francis was trying to regain some of his health, in particular to alleviate some of the serious pain of trachoma, an affliction that infected his eyes to such an extent that for almost two months he found it unbearable to see the light of day and the glow of the fire in the night air. The morning after a terrible night, besieged by a multitude of annoying mice that, almost like a symbolic plague, climbed onto his bed, his little table and his battered body, the Poverello had the happy revelation that “hope does not disappoint,” the certainty that in trust and fidelity in tribulations he was on the true path, following the path of Christ’s passion; While praying to the Triune Lord God, a voice clearly confided to his spirit: “… you must feel as much at peace as if you were already in my kingdom” (Legend of Perugia 83; FF 1614 [1591]). In the greatest poverty, in the greatest dispossession, where those sufferings that can only be seen as a unique loving offering of the complete surrender of his being hardly remain, Francis of Assisi discovers the intense light of God’s love that grounds his hope. I believe the words of the papal bull for the 2025 Jubilee, which quote Saint Paul and Saint Augustine, can better explain this convinced vision, shared by the well-known troubadour of Assisi and Pope Bergoglio, the two Francises:

“Christian hope, in fact, does not deceive or disappoint, because it is founded on the certainty that nothing and no one will ever be able to separate us from divine love: ‘Who then will be able to separate us from the love of Christ? Will tribulations, distresses, persecution, famine, nakedness, perils, the sword? (…) But in all these things we have the complete victory through him who loved us. For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor principalities, neither things present nor things to come, nor spiritual powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation will ever be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Romans 8:1-2). 35; 37-39). This is why this hope does not yield in the face of difficulties: because it is founded on faith and nourished by charity, and thus enables us to move forward in life. Saint Augustine writes in this regard: “No one, in fact, lives in any kind of life without these three dispositions of the soul: believing, hoping, loving” (Spes non confundit, 5).

Thus, on that morning in 1225, in the vicinity of the Convent of San Damiano, just over a kilometer from the southern wall of the city of Assisi, located on the gentle slope of Mount Subasio, with his “simple eye,” despite his trachomatous blindness, and with that sick, weak, and wounded body, which “was entirely flooded with light,” Brother Francis burst into an irresistible joy that led him to compose the Canticle of Brother Sun (FF 263), “for the praise of God, for our consolation, and for the edification of our neighbors,” according to the account in Mirror of Perfection. This biographical source continues that “he set these words to music and taught his companions to recite and sing them.” Also known as the Canticle of Praise of Creatures, this text is perhaps, in the history of the diverse corpus of Italian literature, the first non-anonymous poetic composition composed in the vernacular, more specifically in the Umbrian dialect. To quote it, I turn to the Spanish translation by Lázaro Iriarte, ofm. cap. It begins thus:

“Most High, almighty, good Lord:

Yours are the praise, the glory, the honor, and all blessing;

To You alone, Most High, they are due,

and no man is worthy to make mention of You.”

The beginning of the poetic canticle is inevitable and necessary, but at the same time it reveals the manifestation of a conscience that knows it is limited in its ability to recognize in its fullness the infinite, loving wonder of God, always generous and lavishing all good, the supreme good, the total good (cf. Praises to be Said at All Hours, FF 265). Despite this awareness, the Canticle continues unstoppably with laudatory expressions that express a celebration in union with creatures, beginning, as the first vision of the journey toward our common home, with the magnificent sun, which the troubadour of Assisi addresses with special honorific treatment as “my lord”; its intense, radiant, and warm light is impossible to see directly, as if in an allusion to the elusive and prodigious, inexhaustible, and eternal grace of the divine. But the lucid Francis also sings alongside the elements of Creation in a fraternal, close, and horizontal way, seeing and feeling each creature as a sister who inhabits the same family home. He does so without sublimating or symbolizing, avoiding imposing ego projections on them. He describes and appreciates them in their being, in direct contemplation of their form and their sensitive and also suggestive effects, we could say in an objective way, just as they are: in their existence. An existence that is “very good,” as Genesis reminded us, the goodness that refers us to the Creator and speaks to us of Him, so that the being of each creature is also praise of His glory: “Praise be to you, my Lord, with all your creatures, especially through our Lord, brother sun…”, “through our sister moon and the stars,” “through our brother wind and air,” “through our sister water,” “through our brother fire,” “through our sister Mother Earth.” With this last delicate maternal reference associated with the earth where we remain and work, it moves us to think about the communion that our dwelling signifies—a word that, as Heidegger points out, implies attending to and looking after the being of man and leading him to peace, to freedom, caring for his essence—and also about accepting the gift of existence and the natural cycle of living beings, which includes “sister bodily death,” since our sister-mother earth “sustains and governs us, / and produces diverse fruits with showy flowers and herbs.” In addition to a new contemplation directed toward created things that (re)discover the beauty of their being and their existence, which are praise and communion, does not, with this fraternal language and humble spirit, Francis introduce us to acting in the desirable way of treating us with respect and courtesy, directed, of course, first of all to the Almighty, but also to every human being, to every creature, to the entire Creation? The encyclicals Laudato si’ and Fratelli tutti by the late Pope Francis, inspired by the texts and life of the Poverello, confirm precisely this meaning, while calling us to awaken our attention and try to heal the four ruptures of man that are hinted at in the fraternal references of the Canticle. But there is something more. Éloi Leclerc has written a beautiful and illuminating study of this poem by Francis of Assisi, Le Cantique des créatures ou les symboles de l’union (1970; translated into Spanish by José Luis Albizu as El cántico de las creatividades in 1977), which allows us to consider the configuration of a way of being:

“The Canticle of Brother Sun, far from being simply an accompaniment or ornament of an existence, celebrates an intimate becoming whose meaning is the total reconciliation of man with the world, with himself, and with God. And it’s not enough to say that it is the expression of reconciliation, because it is part of the spiritual experience itself, where it plays a determining role. Here, song is existence.”

Leclerc rightly takes a few verses from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Third Sonnet to Orpheus (1923) to try to explain what he finds in Francis’s poem, which is revealing. Il Poverello, in entrusting his brothers to also sing and spread the Canticle of Brother Sun when they went out to preach, told them: “For what are the servants of God, if not minstrels who must lift and move the hearts of men toward spiritual joy?” By defining the value of the word “minstrel” in this way, he encapsulates the discovery, the meaning, and the irrepressible mission of the Canticle. Following this perspective, reading from Rilke’s verses—whose translation my dear friend Luis Miguel Isava sent me—the Canticle, the fruit of the revelation that Francis shares, is much more: “it is not desire / nor the courtship of something finally conquered. Song is existence”; like a nature that becomes fuller in its being and existence when it can be concretized in an image that is at once love and an expression of love, just as the act of elemental breathing reveals that we are alive. Song and its doctrine are not the learning of letters, commandments, and instructions, although this may be considered an acceptable convenience when beginning to walk, but rather a living of surrender and expectation (cf. Galatians 2:20). Therefore, Rilke’s poem continues with a piece of advice: “It is not a question, O Young Man, of loving, even if / the voice forces you to open your mouth, —learn / to forget that you broke into song. That is passing. / Truly, singing is another breath. / A breath around nothing. A blowing in God. A wind.” Don’t these terms resonate with us, as we associate them in our vision with the divine breath upon the waters in the first verses of Genesis, the same with which the Creator breathed life into man; with the gentle breeze that brought the prophet Elijah out of the cave; the breath of the resurrected Jesus upon the apostles to bestow upon them the Holy Spirit? Isn’t it the experience of the Spirit in Francis of Assisi that makes the expression of the Canticle of Brother Sun possible? To love is like breathing, a fusion of song and life. Singing is another breath identified with being and existence. “I am, moreover, I am. I breathe” is also a celebratory verse by the Spanish poet Jorge Guillén, from his book with the coincident title Canticle (1928).

But, as we mentioned above, the reconciling joy of the Canticle of Brother Sun tends to be shared, which alludes in a general sense to the experiential causes that, assumed in a loving offering, gave rise to its composition: bodily pain and suffering and the wounds and anguish of human coexistence, almost always inevitable. The fusion of these two ruptures is precisely the love of Christ. Thus arises the praise that extends to celebrate those who, despite difficulties, seek to build a harmonious community and reflect the serenity that calms their hearts and also those of their neighbors:

“Praise be to you, my Lord, through those who forgive for your love,

and endure sickness and tribulation;

blessed are those who bear it in peace,

for through you, Most High, they will be crowned.”

The connection with the Beatitudes is clear, especially the one addressed to the merciful, the persecuted, and those who work for peace. The same peace that Leo XIV reminded us of in his first greeting, the unarmed and disarming peace that the risen Jesus gives us and that we strive joyfully to build. The last stanza of the Canticle of Brother Sun encapsulates the joyful imperative of this way of life as pilgrims of hope, whose center is Christ:

Praise and bless my Lord,

and give thanks and serve him with great humility!

(EN)

(EN)

(ES)

(ES)

(IT)

(IT)