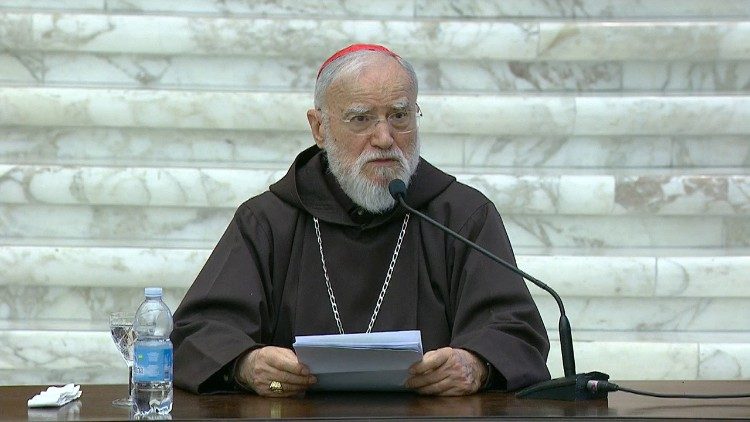

On Friday, March 12, 2021, in the Paul VI Hall, the third sermon of Lent was presented by the Preacher of the Papal Household, His Eminence Cardinal Raniero Cantalamessa, O.F.M. Cap.

The theme of the Lenten meditations is: “But who do you say that I am?” (Matthew, 16: 15) – Christological dogma, font of light and inspiration”. The final Lenten Sermons will take place on March 26.

Raniero Cantalamessa, ofmcap

“BUT WHO DO YOU SAY THAT I AM?

Jesus Christ “true God”

Third Sermon, Lent 2021

Let us briefly call to mind the subject and spirit of the present Lenten meditations. Our purpose has been to react to the very widespread tendency to talk about the Church ‘etsi Christus non daretur, as if Christ did not exist, as if everything could be understood irrespective of him. Yet we have been meaning to react to that in an unusual way: not by trying to convince the world and the media of their mistake but by renewing and intensifying our faith in Christ. Not by way of apologetics, but of spirituality.

To talk about Christ, we have chosen the safest way, the dogmatic one: Christ true man, Christ true God, Christ one person. The way of the dogma is not old and outmoded. As Kierkegaard, one of the main existential thinkers, put it: ‘The dogmatic terminology of the early Church is like a fairy castle, where the most handsome princes and the most beautiful princesses rest. You only have to wake them up, for them to jump up in all their glory.’[1]

Well, that is the key: reawakening dogmas, infusing life into them again, just as when the Spirit entered Ezechiel’s dried bones and they ‘came to life and stood on their feet’ (Ez 37:10). Last time we tried to do that in relation to the dogma of Christ ‘true man’; today we want to do the same with the dogma of Christ ‘true God.’

The dogma of Christ ‘true God’

In 111 or 112 A.D. Pliny the Younger, governor of Bithynia and Pontus, wrote a letter to the emperor Trajan, asking him for advice on how to behave in the trials staged against Christians. He writes to the emperor, ‘on the basis of the information gathered, all they were blamed for and all they did wrong was meeting on a set day before dawn to sing by alternate choirs a hymn to Christ as a God’: carmen Christo quasi Deo dicere.[2] We are in Asia Minor, a few years after the death of the last apostle, John, and Christians already proclaim the divinity of Christ in songs! The faith in the divinity of Christ is born with the birth of the Church.

Yet, what remains of that faith? First of all, let us summarize the main aspects of the history of the dogma of the divinity of Christ. The latter was solemnly established by the Council of Nicaea in 325 with the words we repeat in the Creed: ‘We believe in one Lord Jesus Christ… true God from true God, begotten not made of one substance with the Father.’ Apart from its wording, the deeper meaning of the Nicaean definition, as can be gathered from saint Athanasius, who was its most authoritative witness and interpreter, was that in every language and every age Christ is to be recognized as God in the highest and firmest sense that the word God has in that language and culture, and not in any derivative or secondary sense.

It took a century for that truth in its radical sense to settle and to be accepted by the whole of Christianity. Once the latest revival of Arianism due to the inflow of the barbarians evangelized by heretics (Goths, Visigoths, and Lombards) had been overcome, the dogma became a recognized asset of the whole of Christianity, both Eastern and Western.

The Reformation left it intact and in fact enhanced its central role; yet it introduced a new element that would later pave the way for negative developments. To react to formalism and nominalism which reduced dogmas to mere virtuoso exercises in speculation, Protestant reformers claim that: ‘Knowing Christ amounts to a recognition of his benefits, not to an investigation of his natures and of the ways of his incarnation.[3] Christ ‘for me’ becomes more important than Christ ‘in himself.’ Objective and dogmatic is opposed to subjective and intimate knowledge; the ‘inner witness’ given to Jesus by the Holy Spirit in the heart of each believer takes priority over the outer witness about Jesus given by the Church and in some cases even by Scriptures themselves.

In that interpretation the Enlightenment and Rationalism found suitable ground to demolish the dogma. For Kant, what matters is the moral ideal proposed by Christ, more than his own person. Nineteenth-century liberal theology practically reduces Christianity to the sole ethical dimension and into the experience of God’s paternity. The Gospel is stripped of every supernatural element: miracles, visions, the resurrection of Christ. Christianity only turns into a sublime moral ideal that can do without the divinity of Christ and even his historical existence. Gandhi who, unfortunately, had known Christianity in this reductive version, wrote: ‘I would not even care if someone were to prove that the man Jesus actually never existed and that what is read in the Gospel is the fruit of the author’s imagination. Because the Sermon on the Mountain would remain true to my eyes.’[4]

The reductionist version of Christianity closest to us is the one made popular by Bultmann, this time in the name of de-mythologization. As he wrote: ‘The formula ‘Christ is’ is false in every sense, when ‘God’ is considered as a being that may be objectivized, whether you interpret that formula according to Arius or Nicaea, in an orthodox or a liberal sense. It is correct if ‘God’ is meant as the event of divine actualization.’[5] In less veiled words: Christ is not God, but in Christ there is (or is at work) God. We are extremely far from the dogma defined at Nicaea. Allegedly one would like to interpret the dogma with modern categories that way, but in fact this is nothing but a way of reproposing, sometimes in the same terms, archaic solutions (those of Paul of Samosata, Marcellus of Ancyra, Photinus), which have already been evaluated and rejected by the conscience of the Church.

If one shifts from what theologians say to what, according to different surveys, ordinary people think of the divinity of Christ, he is left speechless. In the aftermath of a local council dominated by the opponents of Nicaea (Rimini, year 359 A.D.), saint Jerome wrote that the whole world ‘whimpered and was stunned they were Arian again.’[6] We would have many more reasons than he had to whimper and to make his stunned exclamation our own.

Christ “true God” in the Gospels

Now, though, we need to stick to our purpose. Let us leave aside what the world thinks and try and reawaken in ourselves the faith in the divinity of Christ. A faith full of light, not a blurred one, a faith that may be objective and subjective at the same time, that is not only based on belief, but also lived out in practice. Even nowadays Jesus is not interested so much in what ‘people’ say about him, as in what his disciples say about him. The constantly pending question is: ‘But who do you say that I am?’ (Mt 16:15). This is the question we try and answer in the present meditation.

Let us start with the Gospels. In the synoptic ones the divinity of Christ is never openly stated, but it is continuously understood. Let us call to mind some of Jesus’ sayings: ‘the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins’ (Mt 9,6); ‘No one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son.’ (Mt 11:27); ‘Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will not pass away” (this saying is the same in all three synoptic Gospels)[7]; ‘The Son of Man is the lord of the Sabbath’ (Mk 2:28); ‘When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, he will sit upon his glorious throne, and all the nations will be assembled before him. And he will separate them one from another, as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats.’ (Mt 25:31-32). Who, except for God, can claim to be able to forgive sins in his own name and to proclaim himself as the ultimate judge of humanity and of history?

Just as a sample of hair or saliva is enough to reconstruct a person’s DNA, so too only one line of the Gospel, if it is read without biases, is enough to reconstruct the DNA of Jesus, to discover what he thought of himself, but he could not openly say to prevent misunderstandings. Every page of the Gospel literally exudes the divine transcendence of Christ.

But it is John who turned the divinity of Christ into the primary aim of his Gospel, its all-encompassing theme. He ends his Gospel by stating: ‘But these are written that you may [come to] believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through this belief you may have life in his name’ (Jn 20:31), and ends his First Letter almost with the same words: ‘I write these things to you so that you may know that you have eternal life, you who believe in the name of the Son of God.’ (l Jn 5:13).

One day, many years ago, I was celebrating Mass in a cloistered convent. The Gospel passage of the liturgy was John’s page in which Jesus repeatedly uttered his words ‘I am’: “For if you do not believe that I AM, you will die in your sins… When you lift up the Son of Man, then you will realize that I AM’ … before Abraham came to be, I AM.” (Jn 8:24,28,58). The fact that the two words ‘I AM,’ against any grammar rule, were written in capitals in the lectionary, certainly in combination with some other mysterious cause, ignited a spark. That word ‘exploded’ inside me.

I knew, from my studies, that the John’s gospel contained quite a few ‘I Am’, ego eimi, uttered by Jesus. I knew it was an important element for his Christology; that through them Jesus assigns to himself the name that in Isaiah God reserves for himself: ‘To know and believe in me and understand that I am he’ (Is 43:10). Yet my knowledge was bookish and motionless and did not arouse any special emotions. That day it was something quite different. We were in Eastertide and it sounded as if the Risen one himself proclaimed his own name before the heavens and the earth. His ‘I Am’ enlightened and filled the universe. I felt so small, like a spectator who is witnessing by chance and in silence a sudden and extraordinary scene, or a great natural wonder. It was a simply emotion of faith and nothing more, but one of those which, once gone, leave an indelible mark.

The Spirit of Jesus enabled John to accomplish an astonishing feat. He embraced the themes, symbols, expectations, in sum, all that was religiously alive, both in the Jewish and in the Hellenistic world, so that all this may serve one idea, better one person: Jesus Christ the Son of God and the Savior of the world. He learnt the language of his contemporaries, to be able to shout in that language, with all his strength, the only saving truth, the Word par excellence, ‘the Word Incarnate.’

Only a revealed certainty, which is backed and sustained by God and his Spirit, could possibly unfold in a book with such insistence and consistency, starting from thousands of different points and always getting to one and the same conclusion: that is to the full identity of nature between the Father and the Son: ‘The Father and I are one” (Jn 10:30). ‘One,’ in the Latin neutral form unum, mind you, that is one thing one nature, not one person (masculine unus)!

“Corde creditur: one believes with the heart”

Just as we did for the humanity of Christ, so too we can now show how the ancient dogma regarding his divinity, while retaining its objective and ontological dimension, is able to encompass and enhance the value of the modern subjective and functional view. Doing the opposite, on the other hand, had proven quite difficult. To the dialectical logic of “either-or”, let us oppose the Catholic one of “et-et”.

None of the so-called ‘Christologies from below’, such as those, to be clear, taking Jesus as an ‘eschatological prophet and the highest revealer of the Father’ as their starting point, or Jesus as ‘a man in whom the awareness of God has reached its highest level’ (F. Schleiermacher), or Christ as ‘a human person in which divine nature subsists” (not a divine person subsisting in human nature!): none of these Christologies, I repeat, has managed to reach the goal of embracing the true mystery of Christian faith and to safeguard the full divinity of Christ. The reason for that failure is explained by Jesus and was well grasped by John reporting it: ‘No one has gone up to heaven except the one who has come down from heaven, the Son of Man’ (Jn 3:13). It is indeed possible for God, if he so wishes, to become man but not for man to turn into God!

|

Saint Paul says: ‘For one believes with the heart and so is justified, and one confesses with the mouth and so is saved.” (Rm 10:10). ‘Faith arises from the roots of the heart,’ in Augustine’s comment.[8] In the Catholic view, just as in the Orthodox one, as well as later from a Protestant perspective, the profession of the right faith, orthodoxy, that is the second phase of the process, has often become so important as to overshadow that first phase taking place in the hidden depths of the heart. All the treatises on faith, De fide, written after Nicaea, deal with the orthodoxy of faith; nowadays one would say with the fides quae, not with the fides qua, with the things to believe and not with the personal act of believing.

This very first act of faith, precisely because it takes place in the heart, is a ‘singular’ act, which cannot be performed but by the individual, in absolute solitude with God. In John’s Gospel we hear Jesus repeatedly asking the same question: ‘Do you believe?’ (Jn 9:35; Jn 11:26); and every time this question elicits from the heart the cry of faith: ‘Yes, Lord, I believe!’

We also need to accept to experience that moment, to undergo that examination. If one immediately answers Jesus’ question ‘Do you believe?’, without thinking: ‘I certainly believe’ and even finds it strange that a believer, a priest or a bishop, should be asked that question, it probably means that they still haven’t discovered what believing really means, that they have never experienced the great vertigo of reason preceding faith. The divinity of Christ is the highest peak, the ‘Everest,’ of faith. Believing in a God who was born in a stable and died on a cross! This is much more demanding than believing in a distant God who can be imagined by anyone as they like.

It is necessary to start by demolishing in us believers, and in us as men of the Church, the false persuasion that we are fine in terms of faith, and that perhaps we still need to work on love. It may be good after all, at least for some time, not to want to prove anything to anyone, but to deepen the inner appreciation of faith, to rediscover its roots in the heart!

We need to recreate the conditions to restore the faith in the divinity of Christ, to replicate the outburst of faith which gave rise to the dogma of Nicaea. The body of the Church once produced a supreme effort, in which, in faith, it rose above every human system and every resistance of reason. The tide of faith once rose to the highest level and its mark was left on the rock. Yet it is necessary for the tide to rise again, since the sign is not enough. It is not enough to repeat the Creed of Nicaea; it is necessary to renew the outburst of faith in the divinity of Christ that we had then, and which has remained unequalled through the ages.

The custom of the Church (and not only of the Catholic Church!) provides for a profession of faith by the candidate, before receiving a mandate for teaching theology. That profession of faith often entailed reciting the creed as well as having to teach certain precise things – and avoiding to teach other equally precise things – that at that time in history were particularly sensitive issues. Think of the oath against modernism!

I believe that one thing above all should be ascertained: whoever teaches theology to the future ministers of the Gospel must firmly believe in the divinity of Christ. This should be ascertained through frank and fraternal discernment, rather than through an oath. After the Second Vatican Council (certainly not because of the Council!) there was a whole generation of priests leaving the seminary and getting to be ordained with very confused and blurred ideas on that Jesus whom they had to proclaim to people and to make present on the altar at Mass. I am convinced that many a crisis in priestly life started and still starts there.

Ecumenism and evangelization

What we have highlighted so far also has important consequences for Christian ecumenism. Two kinds of ecumenism are possible: the ecumenism of faith and that of incredulity; one that unites all those who believe that Jesus is the Son of God and that God is Father Son and Holy Spirit, and one that unites all those that are content with ‘interpreting’ these things each in their own way and according to their own philosophical system. It is a kind of ecumenism in which, at most, all believe in the same things because no one really believes in anything, in the deep sense of the word ‘belief.’

The fundamental distinction of the spirits, in the realm of faith, is not between Catholics, Orthodox Christians and Protestants, but between those who believe in Christ Son of God and those who do not believe in him; in saint Paul’s terms, ‘all those everywhere who call upon the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, their Lord and ours’ (1 Cor 1:2) from those who do not call upon that name.

A new and invisible unity is under construction, which runs across the different Churches. Such invisible spiritual unity is in turn in vital need for the discernment of theology and of the Magisterium, to prevent it from falling into the danger of fundamentalism and of unrestrained subjectivism. And yet, once that temptation has been overcome, one cannot afford to ignore it.

A genuine ‘spiritual ecumenism’ does not only consist in praying for the unity of Christians, but in sharing the same experience of the Holy Spirit. It consists in what Augustine calls the ‘societas sanctorum,’ the communion of saints, which at times may regrettably fail to coincide with the ‘communio sacramentorum,’ that is sharing the same sacramental signs.

Faith in the divinity of Christ is important above all in view of evangelization. There are certain metal structures and buildings that fall if one touches a certain point or removes a certain stone. The building of Christian faith is like that, and its ‘corner stone’ is the divinity of Christ. Once that has been removed, everything falls apart and collapses, starting from faith in the Trinity. Who is the Trinity made up of if Christ is not God? It is not accidental that once the divinity of Christ is bracketed, the Trinity is also bracketed.

Saint Augustine said: ‘It is no great feat to believe that Jesus died; this is believed even by pagans and reprobates; everyone believes in that. But it is a really great feat to believe that he has risen.’ And he concluded: ‘Christian faith is the resurrection of Christ.’[9] The same thing must be said of the humanity and the divinity of Christ, which are respectively manifested in his death and resurrection. Everyone believes that Jesus is a man; what makes a difference between believers and non-believers is believing that he is also God. Christian faith is the divinity of Christ.

‘Knowing Christ is recognizing his benefits’

‘Knowing Christ’, said the Reformers, ‘is recognizing his benefits.’ Let us end precisely by recalling some of these benefits, capable of meeting the deepest needs of our contemporaries: the need of finding meaning in life and overcoming death.

It is not true that modern man has stopped wondering about the meaning of life. Some years ago, a well-known intellectual wrote: ‘Religion will die. It is not a wish, nor is it a prophecy for that matter. It is already a fact that is already awaiting its fulfillment … As soon as our generation and perhaps that of our children have passed, no one will ever consider the need to give life a meaning a truly fundamental problem…Technology has brought religion to its twilight’.[10] Surely, the ultimate meaning of life is not an issue for those who have assigned themselves other meanings. As soon as the latter – youth, health, fame – vanish, many people start asking that question again. It is coming up again even more at this time of the pandemic in which men and women, often confined to their homes, have finally had the time to reflect and to ask questions.

There is a painting, one of the most famous paintings in modern art, that visually conveys where the conviction that life has no meaning ultimately leads. On a reddish background, a man runs across a bridge and past two individuals who look like they do not know or care about anything; his eyes are wide open; he cries out with his hands around his mouth in what is clearly a desperate cry. I am speaking, of course, of Edvard Munch’s painting “The Scream”.

Jesus said: ‘I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness but will have the light of life.’ (Jn 8:12). Whoever believes in Christ can resist the great temptation of seeing no meaning in life, which often leads to suicide. Whoever believes in Christ does not walk in darkness: they know where they come from and where they are going and what they are supposed to do in the meantime. Above all they know they are loved by someone and that that someone gave his own life to prove it to them!

Jesus also said: ‘I am the resurrection and the life; whoever believes in me, even if he dies, will live’ (Jn 11:25). And later the evangelist would be writing to Christians: ‘I write these things to you so that you may know that you have eternal life, you who believe in the name of the Son of God […] He is the true God and eternal life’ (1 Jn 5:13, 20). Precisely because Christ is ‘the true God,’ he is also ‘eternal life’ and gives eternal life. This does not necessarily remove the fear of death but gives the believer the certainty that our life does not end with death.

Let something of all this spring back to mind on Sundays when we proclaim the second article of the Creed as we do now:

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

one in Being with the Father.

Through him all things were made.

_______________________________________________

Translated from Italian by Paolo Zanna

[1] Søren Kierkegaard, Diary, II, A 110 (year 1837).

[2] Pliny the Younger, Epistularum liber, X, 96.

[3] Philipp Melanchthon, Loci theologici, in Corpus Reformatorum, Brunsvigae 1854, p. 85.

[4] See Gandhi on Christianity. Robert Ellsberg (ed). Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1991.

[5] R. Bultmann, Glauben und Verstehen, II, Tübingen 1938, p. 258.

[6] St Jerome, Dialogus contra Luciferianos, 19 (PL 23, 181): ‘Ingemuit totus orbis et arianum se esse miratus est.’

[7] Mk 13:31; Mt 24:35; Lk 21:33.

[8] St Augustine, Tractates on the Gospel of John, 26,2 (PL 35,1607).

[9] St Augustine, Enarrationes in Psalmos 120, 6.

[10] In the magazine MicroMega 2, 2000, pp. 187f.