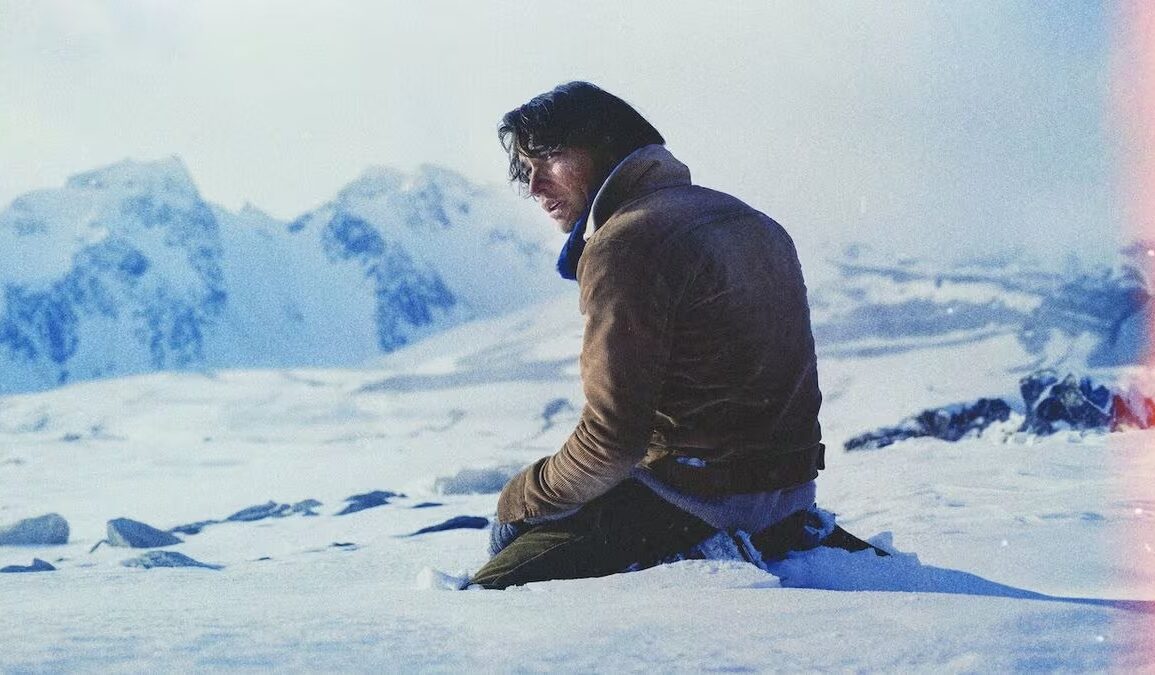

The filmmaker Juan Antonio Bayona revives with his film “Society of the Snow” the aerial tragedy in the Andes, which occurred more than fifty years ago. It is an exemplary story of generosity and resilience that made it possible for human life to make its way, against all odds, in conditions of extreme difficulty. Bayona shows us a path of salvation for human civilization based on donation and care for the most vulnerable. A society to survive in the face of current counter values that entail just the opposite, surviving society.

In the face of calamity, human beings have more reasons for admiration than for contempt. This phrase by the writer Albert Camus in The Plague is replicated in the film The Snow Society, by Spanish director Juan Antonio Bayona, selected to represent Spain at the Oscars and with thirteen nominations for the Goya Awards. About the historic accident of flight 571 of the Uruguayan Air Force that in 1972 was traveling between Montevideo and Santiago de Chile and crashed in the Andes, with 45 passengers – including a young rugby team – of whom only 16 managed to survive, two films have been made: the Mexican film Survivientes de los Andes (1976) and the North American film ¡Viven! (1993). However, Bayona’s cinematographic story, far from being a remake or lengthening the shadow of anthropophagy, has redefined that experience from humanist coordinates that return full relevance and interest to this dramatic event.

The filmmaker emphasizes the model of civilization created by the survivors of the air tragedy during the 72 days and their respective 72 nights, in which they ceased to exist for the world and the search tasks were abandoned due to the infeasibility of being able to resist the temperatures so extreme. This small community had to cut ties with known social patterns and conventions to create a new normal, establish routines and distribute tasks, embracing common values that, in addition to facilitating survival, provided moments of calm, hope and even brief moments of happiness in the midst of suffering.

Bayona emphasizes the power of generosity and human resilience that provokes growing empathy in viewers towards the characters who give the best of themselves and are an exemplary example of brotherhood and care for the most vulnerable. Indeed, generosity catapults giving of oneself without expecting anything in return and, in the film, alludes to authentic donation and dedication towards others and, in particular, towards the wounded and sick. The unconditional love and camaraderie that moves everyone to draw strength to remain together and alive is joined by a deep respect for the different positions adopted by the group regarding the moral dilemma of the possibility of dying if they do not feed on the bodies of the deceased.

Although most of the scenes have been filmed in remote and almost inaccessible places in the Sierra Nevada of Granada, seeking a geography similar to the accident site, there are others that have been filmed in the Andes mountain range, in an area very close to the one where the plane crashed. All of this has required masterful technical skill and achieving the best special effects, which are precisely those that are not perceived as such. Furthermore, both the relatives of the survivors and the deceased have remained in contact with the actors throughout the filming, and some were even welcomed into private homes in order to get to know more closely the human lives that they were going to represent in the film fiction. The film crew held separate meetings with survivors, as well as with relatives and relatives of those who did not survive the tragedy. During the more than fifty years that had passed, and above all, the pain of what had happened had prevented contact and frozen the grieving processes. And precisely in this most private area, not captured by the camera, a story takes place parallel to the film as overflowing with affection, tenderness and humanity as the filmed story itself. As a thank you for the hospitality shown, Juan Antonio Bayona decided to hold a private screening of the film, to which he invited survivors and relatives of the deceased. A total of 360 people together. The director himself has said in interviews promoting the film that this initiative favored a collective catharsis. After watching the film together, everyone was able to applaud in unison, hug each other, cry together and heal both the unprocessed grief and the feeling of guilt of those who returned. The latter were received as heroes when they themselves confessed that they considered themselves miserable. Everyone had imposed a silence on themselves and had not fully recognized what they experienced in the films that until now have recounted the tragedy. Only the book by Pablo Vierci, known to the 16 survivors of the accident, has come close to the lived reality and it has been a challenge for Bayona to turn it into a cinematographic story faithful to this experience.

The film provides a wide thematic range of philosophical and bioethical interest. But, it is worth focusing on Bayona’s proposal on the values that characterize a human society capable of surviving, in the face of countervalues such as selfishness and individualism, growing in our society, which imply just the opposite: surviving a civilization that walks towards extinction. The director of Society of the Snow shows us that human beings can only survive surrounded by peers, following the Aristotelian maxim that only a beast or a God can live outside of society. Bayona also teaches us something else, that a society is not a sum of individualities, nor should we be ashamed of dependence and vulnerability because, precisely, therein lies the strength to embrace our human condition. As one of the survivors, Daniel Fernández Strauss, states, “we were never better people than in the mountains because of the way we gave ourselves to each other.”

Amparo Aygües – former student of the Master’s Degree in Bioethics – Collaborator of the Bioethics Observatory