“It has now become a kind of mantra that vaccines belong to everyone. Indeed, they are health essentials, necessary in many cases for even survival itself.”

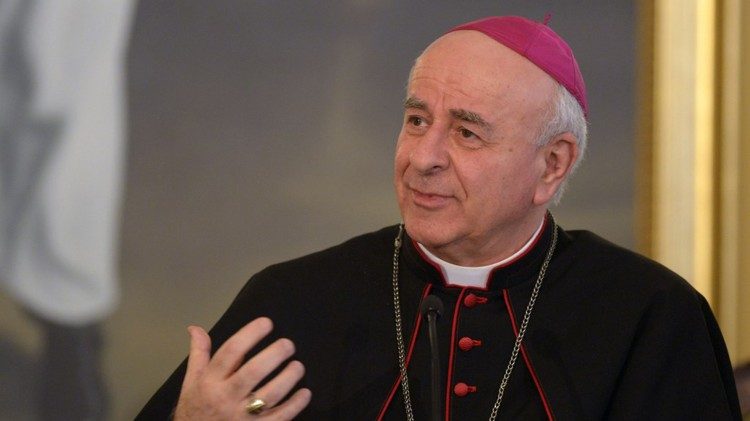

Those were the opening words of Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, president of the Pontifical Academy for Life, at today’s press conference to present the final Statement of the International Round Table on Vaccinations, which took place yesterday, Thursday, July 1, 2021. The Round Table was organized by the Pontifical Academy for Life, the World Medical Association (WMA), and the German Medical Association (GMA).

Archbishop Paglia stressed that “vaccines should be available to everyone and everywhere, without restrictions based on economics, even in low-income countries… We need a commitment from all those taking part in vaccine research, especially since vaccines are delicate and complicated, both from the point of view of the technological resources they require and by reason of the symbolic power that they have.”

The speakers were Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, president of the Pontifical Academy for Life; Dr. Ramin Parsa-Parsi, Head of Department for International Affairs of the German Medical Association, via a live link; and Professor Dr. Frank Ulrich Montgomery, Chair of Council of the World Medical Council, via live link.

The following are their interventions:

Intervention by Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia

It has now become a kind of mantra that vaccines belong to everyone. Indeed, they are health essentials, necessary in many cases for even survival itself. But as Pope Francis often reminds us, vaccinations also affect the common good and justice: “If a pharmaceutical can cure a disease, it should be available to everyone, otherwise injustice will result…there is no place for ‘medical marginalization’.”[1] Pope Francis continues: “Globalized social and economic differences risk controlling the way anti-Covid vaccines are distributed, with the poor always coming last and the right to universal health care, which everyone accepts in principle, being emptied of any real value.”[2]

In addition, vaccines should be available to everyone and everywhere, without restrictions based on economics, even in “low-income” countries. But since vaccines are produced by human genius—and are not an environmental resource spontaneously present in nature (such as air or the oceans) and are not discovered through research (such as the human genome)—to make them available to everyone, specific choices and actions are called for. We need a commitment from all those taking part in vaccine research, especially since vaccines are delicate and complicated, both from the point of view of the technological resources they require and by reason of the symbolic power that they have. In particular, the anti-Covid19 vaccines are very sophisticated products that make use of advanced knowledge coming from different fields of pharmacological research, e.g., oncology. This makes it more difficult to overcome the problems of technology transfer and patent management. We must recognize the significance of these patents, but not absolutize them. The Holy See’s Permanent Observer to the United Nations and Specialized Organizations in Geneva, Archbishop Ivan Jurkovič, made it clear in the context of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) Council, that there is a need to strike a balance between the private rights of inventors (and investors) and the needs of society as a whole. Supporting the universal availability of vaccines means entering into a complex set of problems, which have aspects that are scientific-technological, economic-commercial, and geopolitical (e.g., “vaccine nationalism”’).

What I would like to point out, in particular, are the cultural aspects of vaccines in different societies. Clearly, “vaccination hesitancy,” referred to in our Statement, is a varied phenomenon that has different motivations in different areas of the world. We must be careful not to impose a unitary Western vision on the question. In this regard, I would like to highlight two issues that arise in the globalized world, which I do not think are sufficiently considered.

1. First of all, it must be understood that biological and medical considerations are not the only ones that come into play, that seem objective and immutable. In fact, vaccines have a history that is marked by injustice and oppression. It is difficult to ask for trust from people who have had to deal with systemic victimization by the countries that are generally the ones that produce vaccines. Lots of chickens are coming home to roost in these countries. A one-time effort is not enough. To build real confidence we need policies that include a comprehensive vision of development and fairer international relations.

2. Second, it is not necessarily true that the priorities of the West coincide with those of countries of the Global South (in particular Africa). What seems to us to be a priority is not necessarily a priority for others. We must prevent the Covid-19 pandemic from drawing all attention to itself to a point that it appears, albeit with valid reasons, as the most urgent. We must not forget, for example, that malaria and tuberculosis claim far more victims in Africa than covid-19. But even more important, the lack of basic sanitation and drinking water is a serious threat to health and survival. This suggests to us that we reexamine our research and investment agenda with respect to vaccine production and distribution. It is important that the initiatives were now undertaken in response to the Covid-19 emergency take future needs and structural concerns into account as before and not limit themselves to the short term. In the future, for example, the WHO Immunization Agenda 2030 reminds us, campaigns for vaccinations against other widespread diseases will have to be strengthened since the current pandemic is tending to neglect this point.

The undertaking facing us is complex and will require a lot of work. That is why it is important for us to join forces with all those who share our objectives, even if we have different beliefs from them about other subjects. This framework of synergy on specific objectives that are of great current importance is what the collaboration between the World Medical Association and the Pontifical Academy for Life is based on.

In fact, as I said, it was—before the pandemic broke out—already our intention to have a conference on vaccines in general. Having clearly grasped the importance of the issue back then, we had already started planning. But the difficulties that arose forced us to reduce the size of the meeting, to narrow down the theme, and to conduct the conference as the online Webinar that we streamed yesterday. It can still be accessed online. The follow-on Declaration we are presenting today takes the same approach, and in any case, our original project—a conference that addresses the issue of vaccines in its entirety – has been only postponed, not abandoned—quod differtur non aufertur.

___________________

[1] Francis, Talk to volunteers and friends of Banco Farmaceutico, September 19, 2020.

Intervention by Dr. Ramin Parsa-Parsi

My name is Ramin Parsa-Parsi. I am a physician and head of the international department of the German Medical Association. I am also a member of the Council of the World Medical Association.

Today I am going to tell you the exciting story behind this extraordinary collaboration with the World Medical Association and the Pontifical Academy for Life – specifically how and why we made the decision to host a joint meeting and release a joint statement on the subject of vaccination.

Let me say a few words about the German Medical Association first. The GMA is the central organization in the system of medical self-administration in Germany. Representing all 500,000 registered doctors in matters relating to professional policy, the GMA regulates specialty medical training and continuing medical education in Germany.

What physicians have in common all around the world is the primary duty to promote the health and well-being of our patients. We fight for the equitable provision of care and promote strong and resilient health care systems to be able to provide care of the highest standards.

In this spirit, we have traditionally been very active in collaborating with our international colleagues. The GMA’s partnership with the World Medical Association has always been a cornerstone of these efforts.

Another highly rewarding form of collaboration is cross-sectoral activities which open up new avenues for benefiting our patients.

With partners from other sectors and different areas of expertise, we can complement our knowledge and resources and expand our networks to contribute to the health and well-being of the people we serve.

During the current pandemic, the need for cross-sectoral international collaborations, especially during times of crisis and emergencies, has become even more evident.

But collaborations of this nature were something that we already valued very highly before the pandemic. In fact, the seeds of our meeting yesterday and this press conference today were planted more than two years ago when we – the German Medical Association, Pontifical Academy for Life, and the World Medical Association – agreed to join forces to address the challenges of global vaccine equity and vaccination hesitancy.

We saw the vast opportunities this extraordinary collaboration could provide in our efforts to build trust, raise awareness and achieve broader dissemination of accurate and understandable information on vaccines.

We were initially planning to hold a two-day joint expert conference on vaccination in the spring of 2020 at the exquisite Casina Pio IV at the heart of the Vatican gardens.

And then: The global pandemic hit and the challenges of vaccines and vaccination became even more apparent than ever before.

Of course, as you can see, we didn’t allow the pandemic to stop us: Although we couldn’t go ahead with an in-person meeting as originally planned, we remained determined to make our common voice heard and decided instead to host a condensed two-hour virtual webinar, which was held yesterday.

We are extremely pleased with the successful outcome of it and Professor Montgomery will give a quick summary in a few minutes.

Together with the Pontifical Academy for Life and the World Medical Association we have also released a joint statement which has been published today to coincide with the press conference.

Two key messages are highlighted in the statement, which calls on all relevant stakeholders to exhaust all efforts to:

1. ensure equitable global access to vaccines, which is a key prerequisite for a successful global vaccination campaign, and

2. confront vaccine hesitancy by sending a clear message about the safety and necessity of vaccines and counteracting vaccine myths and disinformation.

The current pandemic has illustrated the importance of vaccination, but it has also laid bare the great inequity of access to vaccines and the dangers posed by vaccine nationalism.

Many developing countries are at a disadvantage due to financial restrictions and limitations on production capacity, while higher-income countries have the resources to access highly effective vaccines.

Unfortunately, there is not yet an adequate supply of vaccines available and, even if vaccine production was increased, it wouldn’t be enough to meet the demands of all regions of the world in a reasonable and timely manner.

Ultimately, vaccines need to be produced locally, but for this to occur several barriers need to be overcome. Solving patent issues is certainly one important element needed to support a self-sustaining system of vaccine production, but this must be bolstered by:

1. The transfer of knowledge and expertise and the training of staff.

2. International investment in vaccine production sites in resource-poor settings

3. The guarantee of adequate quality control

Sadly, there are also countries where vaccines are readily available but subject to skepticism and mistrust.

Vaccine hesitancy is a complex issue. Some reluctance in disadvantaged communities is rooted in historical inequities, breaches of trust in medical research, negative experiences with health care, and suspicion about pharmaceutical companies.

But a more malignant form of vaccine hesitancy is driven by unfounded and misleading claims and myths, including disinformation about side effects.

The best antidote for vaccine hesitancy is building trust, increasing transparency, and addressing communication failures. As trusted voices in the community, medical professionals play a crucial role in this scenario. By working together with the Pontifical Academy for Life, we hope to complement our efforts to generate vaccine confidence by fostering awareness and fighting the spread of myths and disinformation. Furthermore, economically or politically motivated active dissemination of false information regarding the safety and effectiveness of approved vaccines needs to be counteracted.

Improving vaccine confidence is indeed an international challenge that requires international engagement, including the interdisciplinary collaboration of the kind we are engaging in today.

We are very much aware that it is not vaccines that save lives, but rather vaccination. Our collaboration will hopefully help to boost vaccine confidence and to encourage solutions to the hurdles faced by parts of the world where vaccines are still scarce.

Intervention by Professor Frank Ulrich Montgomery

My name is Frank Ulrich Montgomery. I represent WMA as Chair of Council. The World Medical Association (WMA) is the global federation of National Medical Associations representing millions of physicians worldwide. Acting on behalf of patients and physicians, WMA endeavors to achieve the highest possible standards of medical care, ethics, education, and health-related human rights for all people. As such, the WMA plays a key role in promoting good practice, medical ethics, and medical accountability internationally.

Vaccination is life! Since Edward Jenner introduced vaccination to Europe in 1796 – exactly 225 years ago – billions of lives have been saved worldwide through vaccinations. There is probably no other invention in medicine that has saved more lives and prevented more suffering than vaccination. We have eradicated smallpox, we are close to wiping polio off the surface of the earth and deadly diseases like measles have lost their frightening appearance. And science moves on – fast. New biological agents, viruses, and bacteria are emerging, and new bacteria are spread out over the globe in a world of high mobility and increasing populations. Virus and bacteria strike back. They develop variants, mutations or simply develop resistance.

This is a challenge for medicine. We have just proven that we are willing and able to take up this fight. Vaccines against Corona have been developed in record time. Billions of people have already been vaccinated – less than 18 months since we learned about the existence of Sars-Cov2.

We have also learned about gross inequities. Whilst rich, affluent countries urgently started vaccination campaigns, the majority of the world’s population was left behind. Developing nations do not have the technology to develop vaccine production and they don’t have the resources to buy vaccines from the rich producing countries. It is our moral obligation to overcome this outcrying inequity as fast as possible.

And whilst children and their parents, elderly people, and chronically ill in developing countries cry out for help and ask for vaccines, we see a reluctance to get vaccinated and opposition to vaccination in general – without any scientific evidence. The prevention paradox hits us with its full impact. Because we are so successful in preventing disease, people forget the terrorizing sights of large numbers of people dying in endemic or pandemic situations. This brings us into a most cynical position: whereas a child in a developing country is denied a safer life or even survival because its nation or its family cannot afford vaccinations there is also a child in an affluent country that is denied the life-saving prevention because of the ignorance or reluctance of their parents.

There is one more important point about vaccination. It is not only prevention for the vaccinated person self – it also serves the population around that individual. People that cannot be vaccinated or that are not responsive to vaccines are preserved through the simple act of vaccinating others.

As physicians, as leaders in this world, we have an obligation to protect our people. We, therefore, have to offer as much prevention through vaccination as possible in an equitable way and we must undertake all possible attempts to convince “anti-vaxxers” of the advantages and the chances of vaccination.

Our speakers highlighted these issues from different angles. The necessity of vaccination was not challenged but speakers and audience discussed ways to communicate and fight “fake news”. Misinformation is one of the core reasons to vaccine hesitancy. But we also see three vital factors for improving vaccinations: we have to improve Confidence, fight Complacency and deliver Convenience.

Equity is a core issue for international cooperation. 10 Countries in the world have delivered 80% of the 3 billion given doses up to now. And the future is seen in building up production plants for vaccines in low- and middle-income countries as hubs for cooperation and equity. And finally, the philosophical aspects of individual freedom versus common good were highlighted and led to an interesting discussion on the scope of mandatory vaccination.

What do we have to do next:

1) Reach underserved and underinformed communities in a combined effort of science, medicine, and social multipliers such as religious communities.

2) Fight misinformation and fake news.

3) Ensure solidarity.

4) Ensure equity.