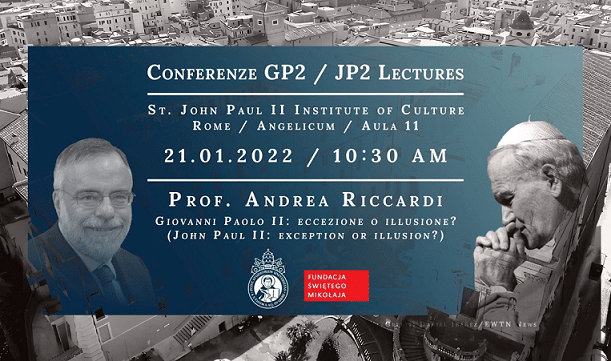

“John Paul II: Exception or Illusion?” was the topic of the January 21 lecture of the “JP2 Lectures” series, organized by the St. John Paul II Institute of Culture at the Angelicum. The lecture was given by Professor Andrea Riccardi (La Terza Università degli Studi di Roma).

Was the pontificate of John Paul II an illusion or an exception in the light of the decline of Christianity between the 20th and 21st centuries?

The question concerns above all the charismatic aspects of Wojtyła’s papacy. The global world likes to identify the Church with the person of the pope and impose a charismatic fulfillment of this role.

The Church of John Paul II, in its various dimensions, was a relevant protagonist in the history of its time, as in the case of the interreligious prayer in Assisi in 1986 or in the transformation in Poland and Eastern Europe. John Paul II began his pontificate in 1978 with an announcement: Do not be afraid! Fear is still one of the most prevalent feelings around the world. It was a direct message to the tired Western Catholicism, intimidated by the successes of secularization. But also to Eastern Catholicism, humiliated by Soviet domination.

It was a geopolitical vision, driven by a mystical passion. Wojtyła did not accept the Cold War division of the world. His pontificate was a time of Church extroversion. In this vision, Europe occupied a central place because, moving out of the realm of fear, set in motion profound religious and social processes, fostering a new culture in the light of religious experience.

John Paul II gathered crowds even in countries where Christianity was exhausted. He believed in the value of dialogue and encounter, of coexistence between religions and different ethnic-cultural identities. He fought for a peaceful transition from the Cold War, showing “strength of spirit”.

We should interpret his figure without isolating him from the history of the Church and understand the complex lesson of his pontificate regarding culture, messianism, faith as a force of change for Christians, the charismatic dimension of the Church with popular and Marian devotion, but also with new communities and movements. He waited and worked to make the Jubilee of 2000 a great opportunity for the Church’s self-reform, to “make the Church the home and the school of communion”.

Professor Andrea Riccardi – born 1950, in Rome. Italian historian, scholar, and politician. He is Professor of Contemporary History at La Terza University in Rome and has also taught at the University of Bari. A number of universities have granted him honorary degrees in recognition of his historical and cultural merits. Andrea Riccardi is known internationally for having founded, in 1968, the Community of Sant’Egidio. In the years 2011-2013, he served as Minister for International Cooperation in the cabinet of the Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti.

Following is the full lecture, provided by the Polish Bishops’ Conference:

Relatively little has been considered about the long, complex papacy of John Paul II in terms of historiography: a full twenty-seven years, even if some of them were marked by illness. While being amply cited by Ratzinger after his election, Pope Wojtyla has gradually slipped into obscurity. During the thirty-year anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Wojtyla’s role received no assessment. Yet Wojtyla’s papacy lasted for a quarter-century of Cold War history and the era of globalization, showing the vitality of Catholicism in various settings, though there was no shortage of problems. This raises the question: was John Paul II’s papacy an illusion or an exception in the decline of Christianity in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries?

One might think it was an illusion, considering that the decline continued in the following decades. But the history is more complicated. Let us look at some indicators. In 1978, there were 250,000 priests in Europe; in 2003, there were 200,000, an actual drop of 50,000[1]. There was, however, an increase in diocesan seminarians between 1980 and 2000: 16,438 in 1980 and 17,611 in 2000. For religious seminarians, the gain was roughly 2,000: from 7,728 to 9,268.

Should the Pope, with his personality and many initiatives, have concealed the crisis rather than tackled its causes? This argument has been made repeatedly. Martini had a mixed opinion on Wojtyla: he acknowledged his great courage, physical as well as spiritual, his strong concentration on prayer, and most of all, “his best moments were his connections with the masses, especially young people.” But he was critical of his government, including his choice of unqualified persons. The Cardinal, setting out the beatification process, noted how John Paul II’s travels and mass events obscured the profile of the local churches, concentrating the world’s attention on the Pope as the “Bishop of the World.”

This observation was primarily made regarding Wojtyla’s charismatic role, with travel playing a decisive part. His personal charisma engaged in the manner of a shepherd, an image popularized by globalization, which tends to focus attention on the leader of a verticalization process. Is such a universalist role of the Pope a usurpation of the bishops, from an ecclesiological perspective? Pope Gregory the Great said as much to John Nesteutes, the archbishop of Constantinople, when he accepted the title of “ecumenical patriarch” from Emperor Maurice: it was “an indiscrete presumption” according to the Pope of Rome at that time.

Indeed, the global world encourages the personalization of the Church as the Pope and almost makes the role into a charismatic service. Thanks to the media and social networks, this is accompanied by a disintermediation process. It should be borne in mind that Wojtyla’s papacy began well before the affirmation of the global world, but the latter presented the problem of overcoming the barriers between West and East, almost encouraging global processes, especially in Europe.

The time of Benedict XVI, a theologist without a charismatic personality, demonstrates the difficulty of managing the papal function. And its restoration in popularity in the early years of Bergoglio was due largely to charisma, which forged a simple and direct relationship with the people, so much so that the question remains of whether the papacy, in the global world, should not be as much as possible a “charismatic government” (the title of my book on Wojtyla)[2]. I note that Cardinal Tauran, the man of the Curia and a critical and institutional spirit, said that a charismatic government was a contradiction in terms. Recent decades, however, have shown the positive features, if not the necessity, of a charismatic Pope to govern such a complex Catholicism.

It should be remembered that the beatification of John Paul II in 2011, six years before his death, by Pope Benedict (who made an exception for the longer time expected for that process partly due to the popularity of the dead Pope’s reputation for sanctity), and his canonization in 2014 by Frances, lie at the origin of the controversy over the overly short procedure. Wojtyla was rebuked for his lack of vigilance on the bishops’ attitude on clerical pedophilia, the problems with funding Solidarność with all their connections, the events involving the Legionaries of Christ, and more. The “National Catholic Reporter,” a leader in this criticism, recommended the American bishops muzzle the cult of Wojtyla as a saint[3].

Clearly, there are various open or unresolved questions about Wojtyla’s papacy. He felt some events to be failures (not to be mentioned), such as the terrible genocide in 1994 in a Catholic country like Rwanda, right when the Synod of Africa was being held. The recruitment of clergy, in any case, did not suffer any significant setbacks. The Pope was firmly opposed to reconsidering celibacy for the ordination of adult married men in the Latin Church. Nevertheless, the Church of John Paul II, in its various aspects that I cannot even allude to here (the Philippines, Chile, Africa, and so forth) was an important leader in the history of his time, including in comparison to the other papacies of the 1900s.

First of all, his papacy fell during the times that Gilles Kepel called the Revanche de Dieu: the new leadership of religions in the public sphere starting in the late 1970s, which was a refutation of the axiom of Western culture in which modernity was leading to the marginalization of religions[4]. The Pope himself was quite aware – as shown by his interfaith prayer in Assisi in 1986 – of the role of religions as an instrument of peace and coexistence, but also – conversely – a tool to legitimize war. As an example of this, one could consider the events in the former Yugoslavia.

After all, Karol Wojtyla and the Church were themselves prominent figures in the changes in Poland and Eastern Europe. The Pope’s funeral in 2005 evidenced his significance to the ruling classes (recall the presence of Iranian president Khatami near the American president Bush), and his religious leadership (Jews like the Chief Rabbi of Tome, Toaff, were present, not to mention Constantinople’s orthodox patriarch, Athens’ orthodox archbishop, and the Anglican Primate), as well as for many common people flocking to Rome. Three million souls attended the funeral near Saint Peter’s Square, and in the previous days another three million had filed by his casket. While some have said that these attendees were a “fragile” fact, a historian would see them as tangible expressions of importance.

It cannot be said that John Paul II’s papacy was an illusory congealment of problems. Those years left a mark on the Church’s history and life. It is rather the Church’s history to account for this, not to repeat it nor to wall it up but to understand it as part of Christianity’s continuity and discontinuity. It is a challenge, however, to filter through his vast, complex heritage, one that resists simplification.

Do not be afraid!

Pope John Paul II made his debut in 1978 with an announcement on fear: like the Easter gospel, it began with urging against fear. He looked to the peoples of the East, oppressed by Communist regimes, and despairing of changes; he turned to Western Christians, daunted by a world that seemed to condemn it to decline in the face of overwhelming secularization. It is remarkable how Catholicism was for centuries a religion of fear, as Delumeau proved in his in-depth research[5]. Evoking death and judgment for a sinning soul was part of a strategy that the historian called personal “overresponsibility”: a system for controlling the conscience as well as an attitude taken toward a life mined with fragilities.

Fear is still one of the most widespread of feelings in a global age, as Bauman noted, while remarking that human beings have never enjoyed as much safety as today, even though there is no shortage of hazards. The global citizen feels exposed to a vast, borderless world where the Other – friend or foe? – could easily find him and take over his space[6].

Pope John Paul II faced fear and resignation articulately, while focusing on his recommendation to share the faith of the apostles of Christ the Risen, who changed his disciples’ lives and made them missionaries of the Gospel. For him, responses to fear were to be found in the Gospel rather than in a collection of political and social reassurances. It was a direct message for a weary Western Catholicism, intimidated by successful secularization. John Paul II thus rejected the idea of restoring the pre-Vatican II Church, which originated with conservatives focused on the human being of tradition who supported Cardinal Siri at the Conclave.

Liberation from fear was an invitation to the Polish people embroiled in a system of intimidation. And his message and presence in Poland ultimately freed those energies of hope, which drove the process leading to the changes in 1989. During the 1980s, the liberating force of Woytyla’s message was seized and released the Poles from the regime’s intimidation tactics, setting free a movement for social change.

Wojtyla, not cowed by the Cold War, envisioned a united Europe. Before his election, he had expressed this in an article in the journal of Milan’s Catholic University, which was headed by his friend Giuseppe Lazzati[7]. His was a geopolitical vision guided by a mystic passion. Wojtyla did not accept Cold War divisions. For him, the real borders of the European continent had been staked by the spread of the Gospel, as it had to the East, so the “continent” thus included Russian and all the Soviet lands. This thereby highlighted two problems: Communism, which firmly ruled the border with the West, and relations with the orthodoxy, especially the patriarchy of Moscow.

Wojtyla’s papacy was an era of internationalist extroversion by the Pope and the Church – remember his travels – but also a time of a certain centrality of Europe. Europe was in fact central to John Paul II’s vision, as he looked upon the world with a conviction that safeguarding Christianity in Europe and European humanity was also vital for the other continents.

The postcolonial era had resized Europe and it had experienced a decline with “repentance and a warning,” he wrote. This involved a decline in the sense of the Church’s mission and of Europe in the world. The Pope, having come from the East, from a non-colonialist Europe that was still in some sense colonized, felt invested in the task of resuscitating the spirit of Europe and making the walls fall, restarting the universalist vision of the Church. Reviving Europe’s spirit, leaving the dominion of fear, set deep religious and social processes in motion. For him, Christianity, even if compressed and persecuted, was an “unarmed” force for change in its social and historical relevance.

It was the “dream of Compostela,” expressed in 1982, asking Europe to recover its origins, to rebuild spiritual unity regarding pluralism, to be a “beacon of civility and stimulus of progress:” “The other continents are watching you,” he reassured them[8]. This was not about European hegemony over Catholicism: in his geopolitics, the Christianity of the old continent had a function and a vocation. In 1991, right from Compostela, Cardinal Martini introduced a complement: “One can say that just as Europe once was the starting point for a widespread evangelization of the world, now the evangelization of the world is tied to the re-evangelization of our continent.”[9]

The cardinal was cognizant of the complex character – not entirely negative for him – of secularization. In his view, it was to be gotten through, while gathering its positive and negative aspects: it was not to be tackled by colliding with it and excommunicating it. The cardinal’s sensibility approached that of Wojtyla: Europe should be “re-evangelized.” Martini, who was sometimes described in the press as “anti-Wojtyla,” constantly measured himself against the Pope’s teachings and had his own original reading of it.

For the Pope, the need was to communicate the Gospel and create a new European culture: “The refoundation of European culture,” he said in Ravenna, “is the decisive and urgent undertaking of our time. Renewing society requires reawakening in it the strength of Christ’s message.”[10] In this, Wojtyla was launching his charismatic authority, a historical sense fueled by messianism, his humanity and abundant energy. John Paul II’s papacy summoned up crowds even in countries with the most exhausted Christianity. More than a few people during his reign noted how his throwing himself personally into the crowd could be an emotional deed rather than a spiritual renewal, making his “passage” lacking in consequences. But it was a reality made of enthusiasm and hope.

Not a decultured faith

Wojtyla, evangelizer, in contact with the piety of the people, however, has the conviction that faith must be consolidated by entering into a process of deep reception, which touches the “heart” but also becomes culture. In 1982, he declared: “A faith that does not become culture is a faith that is not fully received, not entirely thought out, not faithfully lived”[11]. The reception of Vatican II had questioned the so-called “Catholic culture,” which ran the risk of being a counterculture in reaction to contemporary culture. Wojtyla said: “If, in fact, it is true that the faith is not identified with any culture and is independent of all cultures, it is no less true that, precisely for this reason, the faith is called to inspire, to impregnate every culture. A faith that does not become culture is a half-faith.

He was in line with Paul VI’s Evangelii Nuntiandi: “The rupture between Gospel and culture is without a doubt the drama of our age, as it was of others. In Montini there was the idea of the rupture between the world of faith and contemporary culture, born from its separation from faith. John Paul II felt that the Church, by mixing with contemporary reality, could be a creator of a new culture in the light of religious experience. Certainly, a hard core of that culture of which the pope was the bearer, the culture of life, was in sharp contrast with the contemporary feeling. However, this was not all.

The Polish pope, capable of mobilizing feelings, feared a decultured faith, because it was ephemeral, not transmissible between generations, and basically privatized. Significantly, cardinal Bergoglio, Archbishop of Buenos Aires, who has never exaggerated in Wojtylian quotations, strongly emphasized the relationship between faith and culture proposed by John Paul II. He said, echoing Wojtyla, that “a faith that does not become culture is not a true faith.” Wojtyla believed in a “thought-out faith.” In 1998, the pope published an encyclical about philosophy, Fides et ratio, which concludes, “I ask everyone to look deeply at man, whom Christ saved in the mystery of his love, and at his constant search for truth and meaning.”

Modern people like us,” wrote Eliade, “are destined to awaken to the life of the spirit through culture[12]. The scholar of religions was convinced of this, noting the anthropological difference between modern believers and those of previous ages, precisely in their relationship with the world of the spirit.

Certainly, millenary religions represent great cultures (Pio XI called them “religious cultures”). In an experiential and mystical way, Wojtyla recognized the reality of the homo religiosus present in the faithful of all religions. This is where dialogue and encounter come in. In 1986, still in the climate of the Cold War, in Assisi, the pope became the bearer of the culture of interreligious dialogue, convening the leaders of the great religions in the city of St. Francis. It was an original message from a pope who had grasped how, at that time, religions risked becoming an ideology that would sacralize war. He had perceived – Khomeini’s revolution was in 1979 and an “Islamic liberation theology” was spreading – how religions (not only Islam) could become militant ideologies.

In Assisi, the religions, in an atmosphere of dialogue, praying no longer one against the other as had happened in the past, but one next to the other, had to found a civilization based on living together, in which prayer would purify hearts and friendship would replace atavistic enmities. Wojtyla’s proposal was not appreciated by Cardinal Ratzinger, who was attentive to the peculiar mission of the Church in its original Christian identity, fearing that the figure of the pope would become the president of a gathering of faiths all equal and on the same level, giving way to a politically correct dialogue.

Assisi is one aspect of the “new” culture that Wojtyla is producing with his action. For many countries, the reading that the Pope was doing on the history of the nations he was visiting to research their identity: this was valuable in recently founded states with little historical/political awareness. John Paul II was propounding a theology of nations and felt the value of them in history, but brought them together in the preeminent family of nations. Wojtyla’s universalism was tied to the coexistence among religions and different ethnic/cultural identities. The historical dimension, including for nations (see his re-reading of Polish history, which values the seasons of coexistence among Poles, Jews, Lithuanians and Ukrainians), was strongly cultivated in Wojtyla. This can be seen in his last book, Memory and Identity, dedicated to the second World War as well as the nation and Poland[13].

Everything can change!

Wojtyla’s action to awaken the Polish people and channel a movement of liberation from the Marxist regime was conducted with political skill among advances, protests, and cautious arrests. This is an applied “liberation theology” by a pope who, in Latin America, had condemned liberation theologies primarily for their use of Marxism (but how can it be said that Gustavo Gutierrez, a Peruvian liberationist theologian, was a Marxist?). Marxism as an ideology and Marxist systems represented a form of coercion for man, on which Wojtyla did not intend to compromise (even if diplomatic contacts with governments were necessary). If Poland made a decisive contribution to the liberation movement of the East, Wojtyla’s role in Poland was more relevant than is generally noted by political history.

With the Polish 1989, a paradigm consecrated by two hundred years of history is overturned: the great revolutionary changes are accompanied by violence exhibited and, above all, practiced in a more or less intense way. The events of 1989 marked the overcoming of the idea of violent revolution and class struggle. It is well known how, since the 19th century, the Church had felt – for a complexity of historical reasons – the divorce from the working class, which pursued a work of social self-redemption. Actually, in the 1980s, workers, intellectuals, Catholics and the Church fought together in Poland for the end of the regime.

The events of 1989 were a reversal of the paradigm established by the French Revolution of 1789, overcoming violent forms of change: a peaceful transition is possible (this is a path that was later followed in many African countries in the 1990s). Bronisław Geremek, the great Polish historian and protagonist of Solidarity, wrote: “It was a revolution against the Jacobin idea, first of all against its methods, against violence, terror and bloodshed, but also against the centralization of power and the omnipotence of the state…”[14]. He concluded, “The revolution of 1989 dealt the death blow to that of 1789. It put an end to two centuries of French revolution.”

The struggle for peaceful transition -Wojtyla reiterates this in the encyclical Centesimus annus- did not cause deaths but required patience, sacrifice, lucidity and moderation. For John Paul II, this struggle was born -he recalls- from the power of prayer[15]. The Church, by preserving a spiritual and social space, preserved a hope of liberation (and a protected public space). The revolutions of 1989 showed, in a complex political framework full of interferences, the strength of the spirit and of the conscience. In a certain sense they were the expression of the deep spiritual currents that inhabit history, to use an expression dear to Giorgio La Pira, whose spiritual geopolitics resembles that of Wojtyla.

This is the position of another protagonist of the liberation of the East, Václav Havel, with his affirmation of the “power of the powerless,” when he called not to be ashamed of love, solidarity, compassion, and tolerance, “but on the contrary to liberate these fundamental dimensions of our humanity from exile in the private sphere….” Bringing these dimensions into public space was disruptive: it is the liberation of the soul -he says- from totalitarianism, which had annihilated every civil and moral resource. The valorization of the “force of the spirit” and not of violence, as an engine of change, is destined to become the protagonist of many events of the 21st century, which have not always been successful, but have shaken consciences, rallied people, made established regimes tremble. Think of the so-called Arab Spring, which has seen lasting results only in Tunisia. But also, to more recent movements, such as those in Lebanon or Hong Kong, animated by the younger generations.

The layman Havel and the pope were on the same wavelength: “I do not know, if I know, what a miracle is -said Havel welcoming Wojtyla in Prague in 1990-. In the country devastated by the ideology of hatred, the messenger of love arrives; in the country devastated by the government of the ignorant, the living symbol of culture arrives; in the country devastated until recently by the idea of confrontation and division of the world, the messenger of peace and dialogue, of mutual tolerance arrives…”. [16]

Wojtyla’s Christianity showed the “power of the spirit”. How was the Jalta order overthrown? It seemed that only a war -Wojtyla told Frossard- could do it, instead “it was suddenly overcome by the non-violent action of men who, while always refusing to yield to the power of force, were able to find an effective way to bear witness to the Truth. Thus -he concluded- they disarmed the adversary.” [17]

Wojtyla’s idea is a world without walls, which he feels is the intimate ideal of the Church. He noted as early as 1989: “not a few borders tend to close”. Migrants are not only a sociological fact. In them one encounters Christ: “for the believer, welcoming the other is not only philanthropy or natural concern for one’s fellow human being. It is much more, because in every human being he knows he encounters Christ, who is waiting to be loved and served…. “. Ten years later, he, the theologian of the nation, reaffirmed a universalism far removed from national Catholicism: “the Church is by her nature in solidarity with the world of migrants, who, with their variety of languages, races, cultures and customs, remind her of her condition as a pilgrim people… This perspective helps Christians to abandon any nationalistic logic…”. He arrived at a new definition of catholicity. “is not only manifested in the fraternal communion of the baptized, but is also expressed in the hospitality assured to the stranger, whatever his religious affiliation”.

The question of the beginning returns: was the pontificate of John Paul II an exception to the long wave of decline that has been rising since the end of the 1960s? His years cannot be removed from a continuity with the history of the Church that precedes and follows them. However, his pontificate was not the illusion due to a figure of a great communicator, endowed with charisma. The Church has affected history in a unique way in recent centuries. And Wojtyla’s Church has known how to speak to young people projected into the 21st century, leaving behind a new generation.

If there is something unrepeatable in the historical moment, one must, however, also try to read the complex lesson of a pontificate. With his culture, his peculiar sensitivity, his prophetic and Polish messianism, his faith, Karol Wojtyla tried to realize a “Christianity in history” outside the inhibitions of fear and ideologies. He was convinced of the power of change that Christians can introduce into life and history. In 2003, now ill, he told the diplomatic corps: “But everything can change. It depends on each of us. Everyone can develop in himself his own potential for faith, probity, respect for others, and dedication to the service of others.” [18]

The charismatic papacy: a legacy or an exception?

I have defined the pontificate as “charismatic government”[19]. The pope does not renounce governing and uses the institutions of the Curia, but he also gives space to moments and actions, inhabited by a strong charismatic tension: meetings, trips, youth days, pilgrimages, symbolic gestures, gatherings of all kinds, movements, lay people, enhancement of extra-institutional religious initiatives….

His figure does not take off his traditional clothes, he does not move away from the palace of the popes, from the models of his predecessors, from the system of government established by Paul VI, yet he forces the boundaries of papal ritual, of protocol, of the tradition that exalted the continuity of the papacy, more than the personality of the individual pope. John Paul II makes original and symbolic sorties beyond the traditional borders that he does not deny but inhabits with originality. He is a mixture – if we can say so – of “sovereign pontiff”, heir to a long tradition, aware of the ceremonial and administrative aspect of the function, and of charismatic leader, able to use, outside the classical canons, gestures and an original language, made of words, physical expressions, choice of places. He moves between the register of the institution and that of the charism both in his personal role and in the reality of the Church. He guides the institution and favors charismatics.

He remains the pope, but he is a charismatic leader with a strong charge of humanity, as can be seen in his relationship with people: he meets everyone, speaks in the most diverse places, listens, visits as many countries as possible, and introduces the mobility of the papacy. The relationship with the younger generations (a difficult area for the Church since those years) is of great interest. The meetings with young people have been one of the most charismatic aspects of the pontificate, showing a capacity of attraction towards the younger generations.

An acute observer, the great Italian correspondent, Igor Man, wrote in 2000: “Faced with a generation of Western parents who are not very capable of being fathers and mothers, young people have been attracted by the sincerity of the ‘Great Grandfather’, the pope”. The pope is not afraid of stadium cheering, but he does not renounce the originality of his message. He presents himself as weak and sick as he is-for example, in 2000 at World Youth Day in Rome-but inhabited by a spirit that commands respect from young people (even if they do not accept his message in its entirety) as a “postmodern prophet,” to quote Igor Man.

For John Paul II, it is a matter of enhancing the charismatic dimension of the Church. This vision is reflected in his consideration of popular and Marian piety, which he followed by visiting many shrines. There is, in his Marian devotion, a strong understanding of the “charismatic” figure of Mary in the Church. To this aspect, to which he attaches great importance, is added the pope’s attention to the movements that have arisen in a charismatic manner in the Church, which he encourages as an active part of evangelization. The new communities and movements, different realities among themselves, classified somewhat forcibly in this category, represent another conception of the approach to the people and to the territory with respect to the parish. John Paul II, as we have said, was convinced that this group of realities represented an important charismatic space. He recognized its complex and innovative impact at Pentecost 1998:

“the movements officially recognized by ecclesiastical authority are proposed as forms of self-realization and reflections of the one Church. Their birth and spread has brought unexpected and sometimes even disruptive novelty into the life of the Church. This has not failed to arouse questions, uneasiness and tensions; at times it has led to presumptions and intemperance on the one hand, and not a few prejudices and reservations on the other.”

The Pope launched his proposal to the movements and to the Church: “Today, a new stage is opening before you: that of ecclesial maturity”. It was a stage not only for the movements but for ecclesial life, the “communion” between institutional and charismatic aspects. Pope Wojtyla said: “The institutional aspect and the charismatic aspect are almost co-essential to the constitution of the Church and contribute, albeit in different ways, to its life, its renewal and the sanctification of the People of God. It is from this providential rediscovery of the charismatic dimension of the Church that, before and after the Council, a singular line of development of ecclesial movements and new communities was affirmed.”[20]

This affirmation came from the experience of twenty years of pontificate, conducted in the delicate conjunction, not always successful, between the institutional ministry and the charismatic aspect. There is here a theme to be developed in the Church, not identifiable only with the new communities, but also with the new charisms in the life of the communities and in the parishes.

With regard to the new communities, as if in response to the difficulties between movements and bishops, the pope had taken on the relationship with this world directly, in a way similar to that of the papacy with religious in history, binding them to himself. Did the movements and the new communities, as they are at the end of the 20th century, entirely represent the charismatic space, co-essential to the Church and a competitor to renewal? In reality, in Wojtyla there was the idea of a further dynamic to be developed in the Church: in short, something beyond and beyond. In 1983, commemorating the Russian intellectual Ivanov, he said: “In the rich Slavic tradition, it is all the people who are theologians, Christophers…”.

In Latin America, he had perceived the institutional limitation of Catholicism in the face of the growth of neo-Protestant movements. As Hervieu Léger notes, “Catholicism as such is massively perceived as a ‘cold religion,’ normative and administered from above.” And the scholar adds: “Enthusiasm for Catholic personalities out of the ordinary…. is affirmed, if one can say so, in spite of the institution”[21]. The sociologist continues:

“this superficial perception of a grim Catholicism is associated…with the idea that Catholic morality is a morality of repression of pleasure, a morality that constricts, by definition, the fundamental right of each person to achieve his happiness in the ways he chooses.”[22]

Wojtyla intended to overcome these limitations, even if he did not mutilate the message of the Church. The Jubilee of 2000, which he had looked at as a goal since his election in 1978, was for him a great opportunity: it was to be a proposal for the self-reform of the Church. Imbued with messianic visions, he saw the entry into the new millennium as a decisive step. One must look carefully at the papal documents of the Jubilee, Tertio Millennio Adveniente and Novo Millennio Ineunte, in which the hand and thought of John Paul II are strongly felt. The proposal for reform, at the end of 2000, addressed to the Church at the end of the Jubilee was “to make the Church the home and the school of communion“. It was necessary to revisit all areas, including the institutional ones of the Church, in the light of the “spirituality of communion”, transfiguring them. The old pope, as if to reform the Church, stated:

“To this end, we need to make our own the ancient wisdom which, without prejudice to the authoritative role of pastors, knew how to encourage them to listen as widely as possible to the whole People of God… St Benedict reminds the Abbot of his monastery, inviting him to consult the younger members of the community: ‘The Lord often inspires a better opinion in a younger person’. And St. Paulinus of Nola exhorts: ‘Let us breathe from the mouths of all the faithful, for in every believer the Spirit of God blows'”[23].

It was also a challenge to the pastoral governance of dioceses and to a more communal life. The “challenge of the millennium” was to dilate the spaces of communion in a Church that was still pyramidal, letting charismatic and popular expressions grow, exercising the ministry more in listening to the people of God. A proposal that, perhaps, the machine of events of the Jubilee, also propitiated by Wojtyla, had put in the background. Some events, however, marked a strong awareness of the Church, such as the request for forgiveness for the sins committed by the Church and her children, which has behind it a robust theological reflection, without which Catholicism would have faced with difficulty the difficulties of the 21st century. Or, the celebration of the new martyrs at the Colosseum, which highlights in an original and challenging way how the Church of the 20th century is a Church of martyrs.

A reform did not take place, because of the pope’s state of health, but also because it was not considered relevant by the structures of the Church, on which the pope had no power to impose it. This reform, however, had a premise in the recognition of the charismatic space in the Church, without a doubt to be expanded. But it also pointed to the centrality of the Gospel: the pope called for a “return to the Gospel”, almost as if he were distancing himself from the many pastoral programs then cultivated in the dioceses (the culture of the pastoral program goes back to the culture of the plan typical of organizations, including political and trade union organizations, since the 1920s). In Novo Millennio Ineunte, he wrote:

“It is not a question, then, of inventing a “new program”. The program is already there: it is the one that has always been there, gathered from the Gospel and from living Tradition. In the final analysis, it is centered in Christ himself, who is to be known, loved and imitated, in order to live in him the life of the Trinity and to transform history with him until its fulfillment in the heavenly Jerusalem. It is a program that does not change with the change of times and cultures, but that takes into account times and cultures for true dialogue and effective communication.”

The reconsideration of Wojtyla’s pontificate is important in light of the reflection on the decline, which seems to be a reality in our European world and in the life of the Church: the themes of fear, culture as a space for Christianity, charismaticity, the incidence of Christianity in history (“transforming history with it…”-he writes), reform in communion even of diocesan life, finally the return to the Gospel… The reality is that, in some way, Wojtyla’s pontificate, so long and complex, closed without a reconsideration and was not succeeded by a reflection. His legacy was in part articulated in different segments allocated to the most diverse, sometimes contradictory positions. After all, John Paul II has been more recalled by the pro-life movements on issues close to their hearts than for other aspects of his pontificate. But the entire pontificate is the story of more than a quarter of a century of the Church.

[1] Ph. Jenkins, Il Dio dell’Europa, cit., p. 63.

[2] Cfr. A. Riccardi, Governo carismatico. 25 anni di pontificato, Milano 2003.

[3] J. Horowitz, Sainted Too Soon? Vatican Report Cast John Paul II in Harsh New Light in “The New York Times”, 14-11-2020. Cfr pure US bishops, please suppress the cult of St. John Paul II in “National Catholic Reporter”,

Nov 13, 2020. Si veda anche G. Galeazzi e F. Pinotti, Wojtyla segreto, Milano 2011.Un’analisi puntuale sulla vicenda della pedofilia nella Chiesa sul lungo periodo, ma solo sul mondo francese, in C. Langlois, On savait quoi?, Paris 2020.

[4] G. Kepel, La revanche de Dieu. Chrétiens, juifs et musulmanes à la reconquête du monde, Paris 1991.

[5] Cfr. J. Delumeau, La paura in Occidente, Storia della paura nell’età moderna, Torino 1979.

[6] Cfr. Z. Bauman, Paura liquida, Roma-Bari 2008. Id., Il demone della paura, Roma-Bari 2013.

[7] K. Wojtyla, Una frontiera per l’Europa dove?, “Vita e Pensiero”, 4-5-6 (1978), pp.160-168.

[8] Giovanni Paolo II, Atto Europeistico a Santiago de Compostela, 9 novembre 1982 in www.vatican.va .

[9] G. Miccoli, In difesa della fede. La Chiesa di Giovanni Paolo II e Benedetto XVI, Milano 2007, p. 173.

[10] Giovanni Paolo II, Concelebrazione nella Basilica di Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna 11 maggio 1986, in www.vatican.va .

[11] Giovanni Paolo II, Lettera di fondazione del Pontificio Consiglio della Cultura (20 maggio 1982) in www.vatican.va

[12] Cfr. M. Eliade, La prova del labirinto. Intervista con Claude-Henri Rocquet, Milano 1982, p. 60.

[13] Giovanni Paolo II, Memoria e identità. Conversazioni a cavallo dei millenni, Milano 2020.

[14] B. Geremek, L’historien et le politique. Entretiens avec Bronislaw Geremek recueillis par Juan Carlos Vidal , Montricher 1999, p. 397.

[15] Giovanni Paolo II, Lettera Enciclica Centesimus Annus in www.vatican.va .

[16] M. Zantovsky, Havel a life, London 2014, p.385.

[17] Cfr. A. Frossard, Conversando con Giovanni Paolo II, Milano 1989.

[18] Giovanni Paolo II, Discorso al Corpo diplomatico, 13 gennaio 2003, in www.vatican.va .

[19] Cfr. A. Riccardi, Governo carismatico, cit.

[20] Giovanni Paolo II, Discorso ai Movimenti Ecclesiali e alle Nuove Comunità, 30 maggio 1998, in www.vatican.va .

[21] D. Hervieu-Léger, Catholicisme la fin d’un monde, cit., p. 133.

[22] Ivi, p. 134.

[23] Giovanni Paolo II, Lettera Apostolica Novo Millennio Ineunte, in www.vatican.va .