Antonio-Carlos Pereira Menaut is a Spanish constitutionalist, well-versed in political theory and an attentive observer of cultural contemporaneity. I met him in Piura, where he was a visiting professor at Udep for several seasons. His Anglo-Saxon training has given plasticity and freshness to his legal and political proposals. I have used his book Twelve Theses on Politics quite profitably for my classes on political thought. After years, I came across a recent essay of his, The Society of Delirium: an analysis of the great global reset (Rialp, 2023). A reading of the cultural and social state of our time – rather of European time – from the perspective of the observer who has not renounced common sense and can say that the king is naked. His methodological proposal is very simple: “Trust our reason and our senses, study things more than theories about things, go to the concrete, always go from the known to the unknown, not forgetting that res sunt (things are) and that objective reality exists, no matter how much quantum mechanics and relativism lurk.”

Pereyra Menaut is not only a fervent defender of freedom, but he lives from it. At the beginning of his essay, he points out that “history is not a succession of cause-effect followed automatically by a new cause-a new effect and so on, all of this now visible to us, even if it is with great effort, in the rearview mirror of the centuries. How many times what happened at this or that historical moment was not a mere evolution or necessary consequence of what preceded? How many times have concrete attitudes and actions – again, human freedom – mattered more than theories; not to mention chance, chance and unpredictability. A reflection alien to all determinism of before and now. We are not condemned to perish under the weight of the wave of history. Nor does it have to happen in our latitudes, what is already happening in Europe and the United States. I find the expression that is heard so often “this will also come to Peru” to be an inappropriate defeatism for those who take seriously the creative force of freedom.

Another of our author’s statements, very encouraging for what Chesterton called the common man, is the criticism of all kinds of enlightened people who assume the role of bearer of the last word on various topics when he states: “do not judge; credite expert; the government knows more and the European Union even more; the WHO says this or that; Industrial, agricultural and fishing disarmament is good, although in your ignorance you do not see it; concentrating all production in China is good (now it doesn’t seem so good anymore); The law is the law and it is to be fulfilled; Do not trust your reason or your senses, research from the North American University of X shows that the leaves of grass are not actually green.” It is about recovering common sense and putting things in their place, knowing that there are so many matters still open to high dialogue between scientists and laymen.

Now comes the diagnosis of the present situation. He agree with Pereira Menaut when he indicates that one of the features of European culture is the distancing from God and the consequent loss of the transcendent meaning of life. Added to this backdrop is “a negative and pessimistic stance about man, and, lately—an important novelty—also about the world. It would be the harvest of having sown the loss of the sense of reality, of having denied that res sunt, things, are.” This posture of classical realism towards things supposes an attitude of humility in the human being in his relationship with the environment: what is real is and demands recognition of its peculiar way of being and acting.

Our author continues by pointing out that “of the many virtues and good attitudes that we need, today we need a specific type that no one will give us unless we first see the need for it. We need to counter abortion, the denial of religious (and other) freedom, human trafficking and hypersexualization, but we also need something to counter surveillance capitalism, technocracy, the commercialization of care, the mesh that suffocates us in regulations, the lack of prudence, the intolerance of imperfection, the manipulation of human nature, the conditions that directly and indirectly favor the wave of suicides and so many other problems. We need (…) order, direction, meaning.” It is a good list of tasks whose completion requires optimism and a good dose of quixotic spirit.

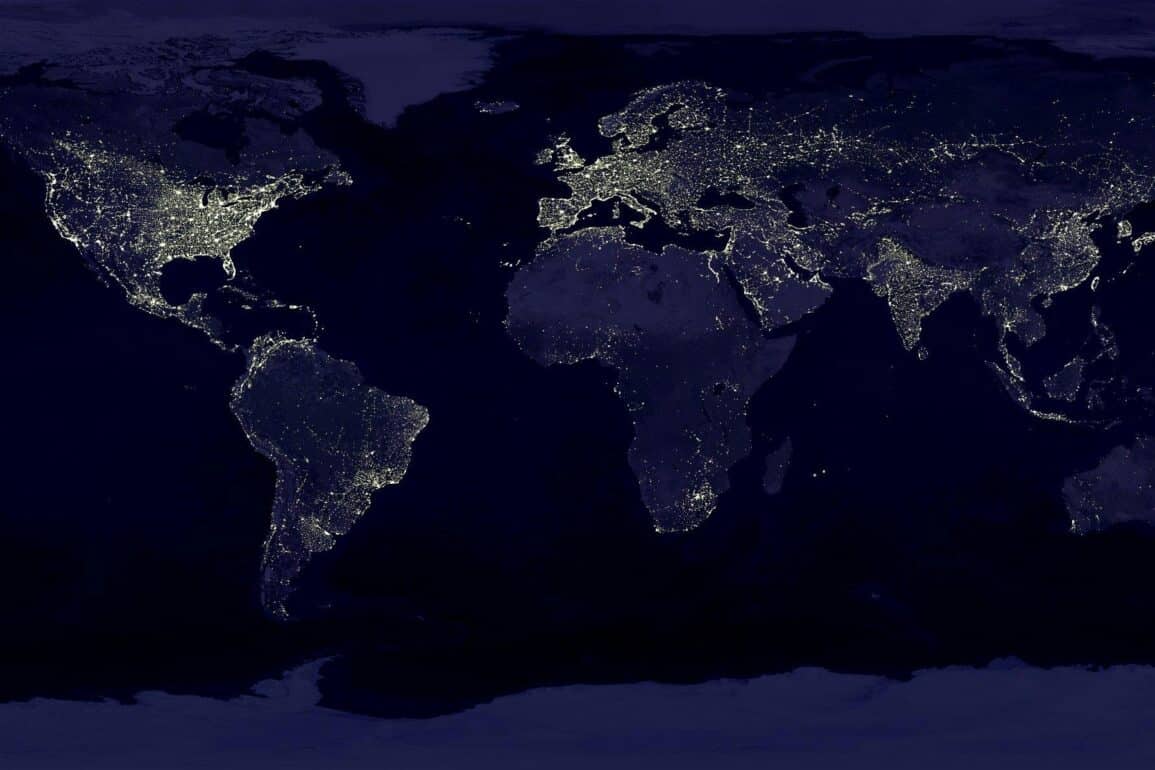

In some aspects, the tone of the diagnosis becomes too gloomy for my taste and I turn my face towards our Peru, a land blessed and blessed in so many aspects, where there are many more lights than in the shadowed Europe with its disorientation in matters of deep significance. . Here we respect human life from its conception. The family maintains its essential features. We also have a deep-rooted religiosity, manifested in so many popular devotions that flood the streets throughout Peru. The mixing of all bloods makes us more inclusive. Gender ideology and cancel culture do not silence the voices of fruitful freedom of expression and conscience. Issues? Many, but also promises whose fulfillment awakens the entrepreneurial spirit of so many generations of Peruvians.

“For that more human, more social and more constitutional future – proposes Pereira Menaut – we need a minimum of family, social, territorial and cultural roots; a minimum of friends—without friends no one could live, Aristotle thought—a minimum of conversations that are not elevator conversations, a minimum of communities of human dimensions; a minimum of stability; of professional work, of being useful, of doing things for oneself, even with one’s hands; a minimum of spaces prohibited from the eye of the state or Google; a minimum of direct relationships with people, not with professional roles (much less with a bot); a minimum of stable relationships, some of them unconditional; “a minimum of serious commitments that give meaning to life.” Not only a more human future, but also a more real, closer, more interpersonal present. I’m up for this good life with an air of Hobbit Shire.